Michel Foucault is a very popular author in chic lit-crit circles at the moment. A full blown postmodernist, his work is a combination of history and philosophy.

In his book Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison, he uses theoretical disciplinary texts to paint a picture of the historical French penal system. He traces its evolution right up into Foucault’s day (copyright: 1977), a time marked by massive and unquestioned use of the prison as the primary recourse of the judicial system.

The book can be viewed as essentially a text on the evolution of power, with the prison as the teeth of that power.

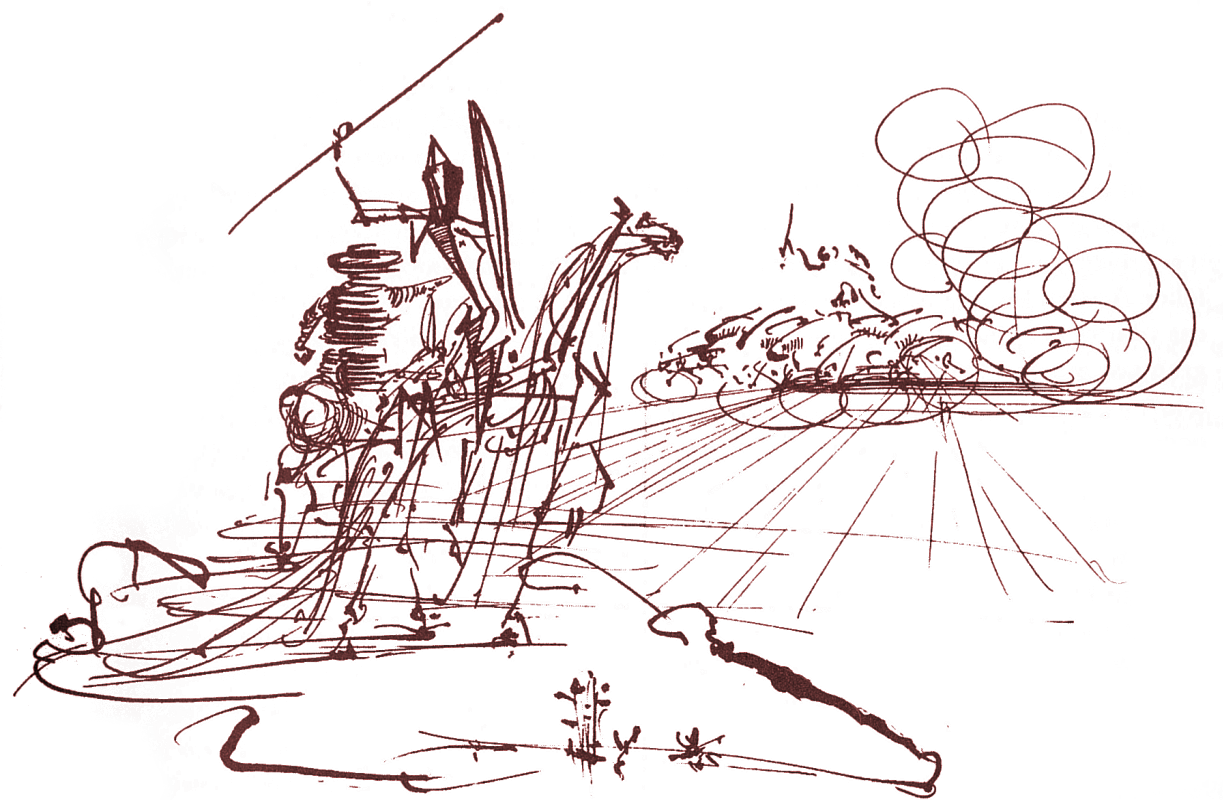

According to Foucault, punishment started out as an extension of the sovereign’s right to make war upon his enemies. As such, punishment was a series of counter-atrocities.

The idea that prisoners are reformable took hold, and, as such, the prison system was born, with its ostensible purpose being to inculcate correct movements into a convict. Thus, through force of habit, the prison system manufactures a reformed and decent member of society. Prisoner’s bodies are conditioned much the way that a soldier’s body is conditioned: with an emphasis on repetitious and exact maneuvers under the strict authority of a drill-master. The body of the delinquent becomes, marionette-like, a spectacle of the power of strings. The body as the site of the inculcation of society’s values is an aspect of society at large. To some extent, those who do not “take” to normalization of this sort are those who end up in prison.

Prisons have not eradicated nor even deterred crime. They have, however, created a class of delinquents who, ostracized by society, become repeat offenders.

This is not viewed as a marginal effect of the prison system by Foucault, but rather, by earmarking the rebellious and those resistant to normalization as “delinquents”, society is able to monitor them and, while in jail, harness their labor. These people would otherwise be masterless vagabonds, unemployed and unwilling to serve society.

The prison serves as a sort of aikido, harnessing this negative societal momentum and utilizing it as cheap labor, preventing this energy from turning political in nature.

Thus was born the Industrial-Prison Complex of today.

I am in no way able to do justice to the subtle themes and bold philosophies of this book. I have highly simplified his arguments here. It is not light reading, in fact, it is often very difficult to read. The sentences are long and windy, seeming to lose their subject amongst the abundant commas (partly due to the translation from French). But I highly recommend it, and its thesis is well worth the effort. It really changed the way I think about society and its systems of normalization.