“I still feel funny watching movies without my wife and kids . . .”

. . . A child is crying and screaming, dragged by her mother away from the visiting room . . .

“I’m going to sleep the day away. Wake me up in two-thousand-six.”

“Reuben, Reuben! Tell Pachengo about my daughter. Tell him, man! Tell him! She wild, dog, wild! Hey listen! She got tired of playing with them. She wanted to be with her Daddy! Reuben, tell Pachengo what she said! Man you gotta understand—I been down six years behind the fence . . . “. . . My cross bunkie, 400 pounds, burps loudly, closing his eyes.

A quote from Discipline and Punishment by Foucault: “There are those for whom glory and abomination were not disassociated, but rather coexisted in a reversible figure”.

What do men live and compete for without women? I have become manic-depressive. And that is a completely normal response to prison. No concerned psycho therapists or prison counselors sit me on their sleek couches and ask me why. And yet on the outside, in that twisted parody of natural human existence, nobody asks whether depression is an apt response to a vapid world, they just dole out the Prozac on the blind assumption that it is the individual’s responsibility to adjust to the system. George Bernard Shaw once wrote, “Reasonable people adapt themselves to the world. Unreasonable people attempt to adjust the world to themselves. All progress, therefore, depends on unreasonable people.”

In prison, the reasonable ones are those whose hopes and dreams have adjusted to this space, the artists who paint in one corner of the canvas. And yet, irrational as I am, I limit my thoughts of freedom, because if I stay there overmuch, I forget to enjoy what I have here: the books, the letters, my spirit, the exquisite cuisine . . . no really.

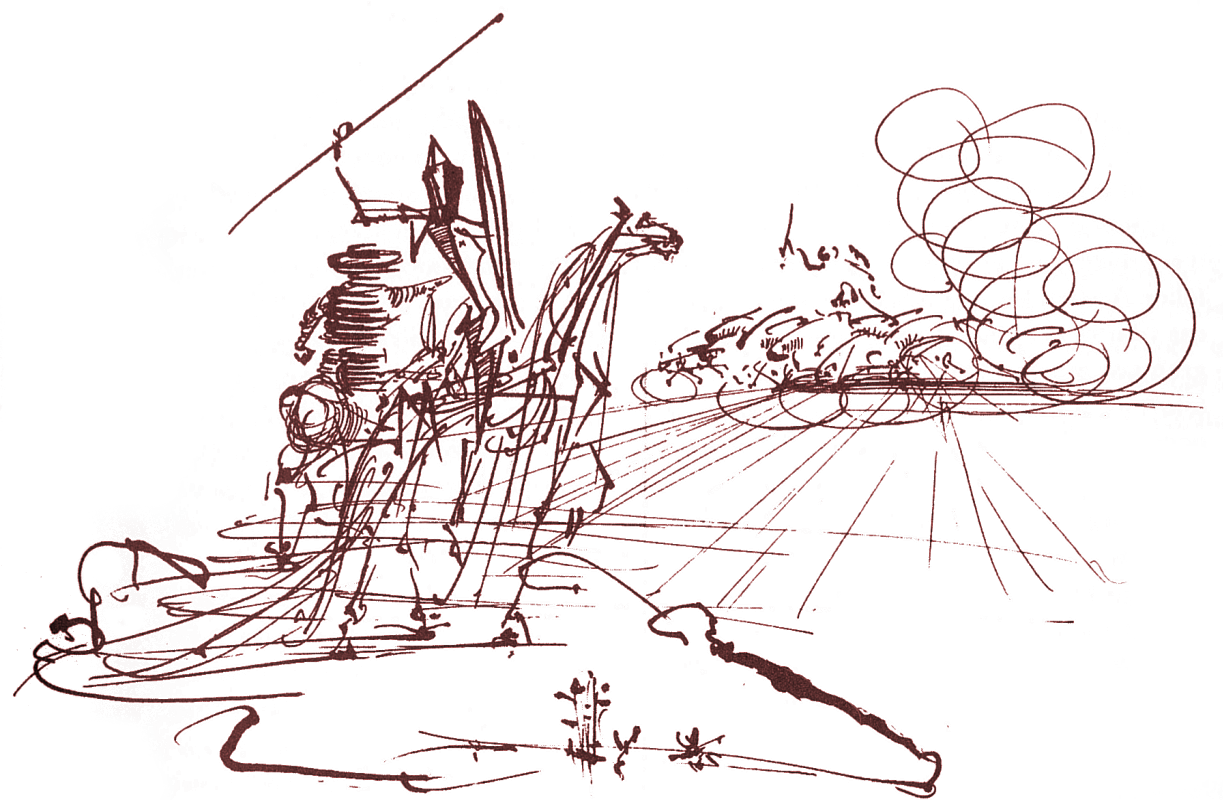

Everyone’s happinesses are in relation to their everyday life: what they consider normal. Good fortune is upward deviation from average existence: for millionaires and for serfs. Here, the most pathetic are the ones who never stopped for anything: eating in the car as they rushed from place to place, now halted. My friend sits and stares for long periods of time: a broken hell-raiser. Men break horses and dogs, but other men? Is prison like the man with the club that beats the wild dog until it licks his hand?

Equally unhappy are the ones who star at Lexuses and women. Those things were taken away. Unfortunately perhaps, they cannot take away the memories, lusts, and shadows. In measuring these things as a part of themselves they have lost a part of themselves. The hardest part for me is being away from Charity. She is still a significant part of my life even though her physical self consists only of words on paper. We write every day.

The inmate’s sadness and maladjustment are due to imprisonment. One then must wonder whether crime itself is the product of a twisted society. And then you are left wondering which are the criminals: the convicted felons or those who perpetrate the counter-atrocity of punishment upon them: the judges, prosecutors and wardens. For after all, the vivisection of families and the caging of human beings is surely a crime. But which is the greater crime, the crime or the counter-crime? Is the answer merely a question of who controls the establishment? Who holds the reins of power?

On another level, laws are perceived to be the wardens of order. Here in prison, there are many rules: you can only have 5 books, 25 letters, and empty food containers are not to be used as cups. Vegetables are contraband. But instead of creating order, the logorrhea of rules fosters a disrespect for rules. It creates an anarchy interrupted by selective enforcement. Since everyone is in violation of some rule or other at all times, enforcement is based upon personal vendetta rather than straightforward non-compliance with the rules. The over abundance of law empowers the arbitrary intervention of power. And this is the state of the laws that govern police intervention too. That is why police are able to enforce such imaginary crimes as “Driving While Black” (DWB), a moving violation that many African-American males are ticketed for.

I read “The Pentagon Papers”, a book of internal government memos regarding the escalation of the Vietnam War. It was interesting to observe the process that the government uses to determine policy. I also read “Dada: Art and Anti-Art” by Hans Richter. I was struck by the way in which artistic movements coalesce and dissolve, gaining legitimacy within a historic context, saying what needs to be said, and then losing relevancy. I thoroughly enjoyed the themes of reason and unreason, order and chaos, chance and design.

Another book I consumed was “Days and Nights of Love and War” by Eduardo Galeano. Galeano was an exiled Uruguayan journalist in the boom days of the military dictators in Latin America. It is a fragmented, achingly beautiful memoir. All the people he laughed and drank with disappeared one by one, hunted down for their “dissidence”. This is the legacy of US military intervention and aid. It tore me up for about 4 days.

Another week closer to the door . . .

Jeremy