I am often puzzled by our culture's need to supersize a story out of the realm where ordinary people can relate to it. Why must we make all things epic? When was the last time you faced an absolute evil that required you to don full chain mail? And so, I was again caught flat-footed by the Peter Jackson Hobbit franchise. Why inject a cosmic battle of good against evil into Tolkiens' humble tale of a hobbit far from home caught in forces beyond his reckoning?

Now look here. I loved Jackson's Lord of the Rings beyond measure, and I thoroughly enjoyed the first Hobbit movie, with just the touch of unease that one feels when settling in to sleep after a too-heavy dinner.

I am a lover of Tolkien. I have eternally boasted that I read "The Lord of the Rings" when I was in second grade. "Lord of the Rings" was proof I was smart. I dressed as Aragorn in a homemade cloak and practiced plastic swordcraft with my brother. I've always felt unmanned by the shadow of Aragorn, that world-wise Dunedain ranger, and I had to prove my manhood in elaborate ways that are not normally required of modern young men: by hitchhiking and civil disobedience. I read Lord of the Rings whenever I feel particularly burdened by life, and Frodo and Sam put my struggles in perspective and lend my life meaning. I am a lover of Tolkien, yes, but I am not a Tolkien purist.

I am a lover of Tolkien. I have eternally boasted that I read "The Lord of the Rings" when I was in second grade. "Lord of the Rings" was proof I was smart. I dressed as Aragorn in a homemade cloak and practiced plastic swordcraft with my brother. I've always felt unmanned by the shadow of Aragorn, that world-wise Dunedain ranger, and I had to prove my manhood in elaborate ways that are not normally required of modern young men: by hitchhiking and civil disobedience. I read Lord of the Rings whenever I feel particularly burdened by life, and Frodo and Sam put my struggles in perspective and lend my life meaning. I am a lover of Tolkien, yes, but I am not a Tolkien purist.

In fact I can tolerate endlessly epic CGI battle scenes, for the most part. And I do not object to plot changes on principle: I'm all for adaptation or even expansion. But yet, there is something soured for me in Peter Jackon's Hobbit. Something that began with the Orc lord Azog the Defiler and his quest to destroy the dwarves.

Tolkien: The Master

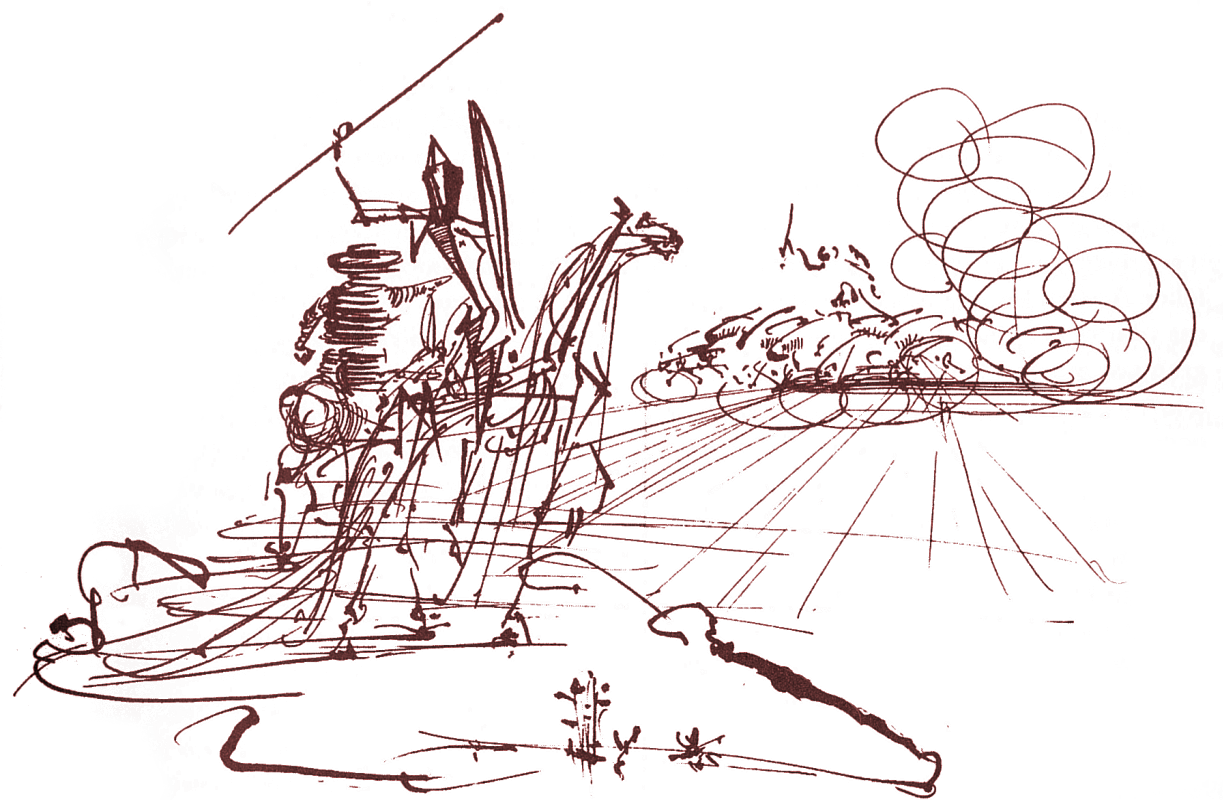

Let us begin with Tolkien's Hobbit. There, the forces of evil are slumbering: evil is like a beehive. It is the dwarves who awaken it, questing to regain their golden kingdom beneath the mountain. Think: the trolls are just eating dinner, when Bilbo tries to pick their pocket and stirs them to seek out roast dwarf. The dwarves seek refuge from a storm in the cave that is in fact the goblin's front porch. It's only by wandering from the Mirkwood forest path that they arouse the ire of both the spiders and the elves (generally good folk stirred up by the dwarves). Finally, Smaug himself is called "That Chiefest and Greatest of Calamities" and is provoked to rage by Bilbo's theft of a single gold cup.

In Tolkien's Hobbit, evil is a hazard of the natural world, summarized by the saying Bilbo invents, "out of the goblin mines and into the trees," which becomes the proverb, "out of the frying pan and into the fire." Evil lies dormant until it is awakened by the incautious or the greedy traveller.

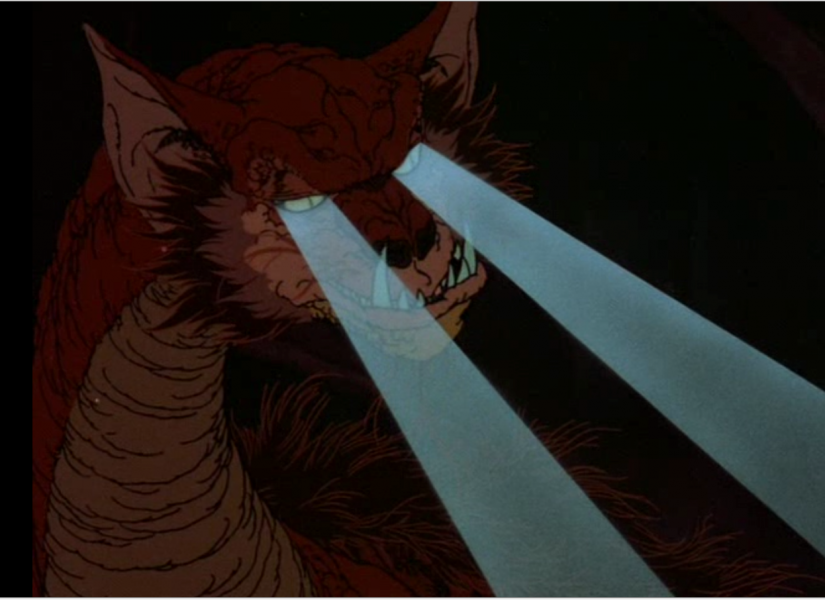

If we want to understand evil in the Hobbit, we must look to that epic evil: Smaug. The dragon slumbering beneath the mountain is an explanation of a volcano, and Smaug himself acts much like a volcano, erupting and then lying quiet for decades. He is a force of nature, drawn irresistibly to the hoarded gold under the mountain like steel to iron ore.

If we want to understand evil in the Hobbit, we must look to that epic evil: Smaug. The dragon slumbering beneath the mountain is an explanation of a volcano, and Smaug himself acts much like a volcano, erupting and then lying quiet for decades. He is a force of nature, drawn irresistibly to the hoarded gold under the mountain like steel to iron ore.

On the other hand, goodness in Tolkien's Hobbit is represented by Bilbo, who offers up his entire share of the treasure to avert senseless war so as to return to his home and hearth. Bilbo values the everyday, the simple pleasure of daily life over wealth and war. Goodness is driven by a simple love of the ordinary hearth and home, and by contrast, evil is awakened in good elves and bad orcs alike by a greed that is not content with the domestic, instead, it wishes to possess the infinite in the form of treasure.

Jackson: The Pretender

But Jackson's Hobbit contrasts this: there is in the introduction of Azog something of evil beyond that which we awaken in ourselves. Azog is acting like fate itself, moving the plot forcefully towards a climactic clash of good and evil that goes beyond Tolkien Hobbit's mere lure of unguarded treasure. Azog becomes the central evil rather than the hoarded gold itself.

But why must we continually invent an evil that is beyond us? Why can we not accept Tolkien's most simple formulation of evil as that which is awakened in us, drawn by the lure of wealth, and only destroyed by renouncing the wealth itself in favor of the spiritual richness of the ordinary?

The Dragon Within Us

This is the state of our culture, which has created the demand placed upon Hollywood by movie consumers. The United States has sought solace in the black-and-whiteness of fantasy and science fiction ever since the 911 terrorist attacks and the invasion of Iraq. There is something in the murkiness of the war on "terror" that commands us to invent clear-cut struggles of good and evil.

It's not enough that we have awakened the dragon of climate change by delving deep into the mines of the earth for gas and natural gas. No, we must invent a foe to shadow us. For we cannot be the shadow ourselves, we must invent one to lend our exploitation of the earth the breadth and depth of a war against evil. But we flatter ourselves by inventing an absolute evil beyond ourselves, implying that we ourselves are an ultimate good.

It's not enough that we have awakened the dragon of climate change by delving deep into the mines of the earth for gas and natural gas. No, we must invent a foe to shadow us. For we cannot be the shadow ourselves, we must invent one to lend our exploitation of the earth the breadth and depth of a war against evil. But we flatter ourselves by inventing an absolute evil beyond ourselves, implying that we ourselves are an ultimate good.

The truth of the matter is that the evil is within us, and it cannot be externalized as Azog the counter-questing orc or as freedom-hating terrorists. Nor can it be resolved in an epic battle of Five Armies. It is fought within Bilbo and Thorin as they struggle against their own selves: who will be master, me, or the dragon within me? Can I be content with the ordinary? Can I love the everyday?

The thing is, we don't get more just by stuffing the plot fuller and fuller like a burger with extra fries. When we do, we fall prey to our own parable, the parable of Thorin, choking on his own greed, unsatisfied with a mountain of treasure and seeking after the Arkenstone, a monstrous gem which is nothing more than a symbol of conspicuous consumption. And ironically, because the Arkenstone cannot truly be traded for anything less than a kingdom, it is un-exchangable for anything real.

In the end, the struggle of good and evil in Jackson's Hobbit was like the Arkenstone: totally un-exchangeable for the real.