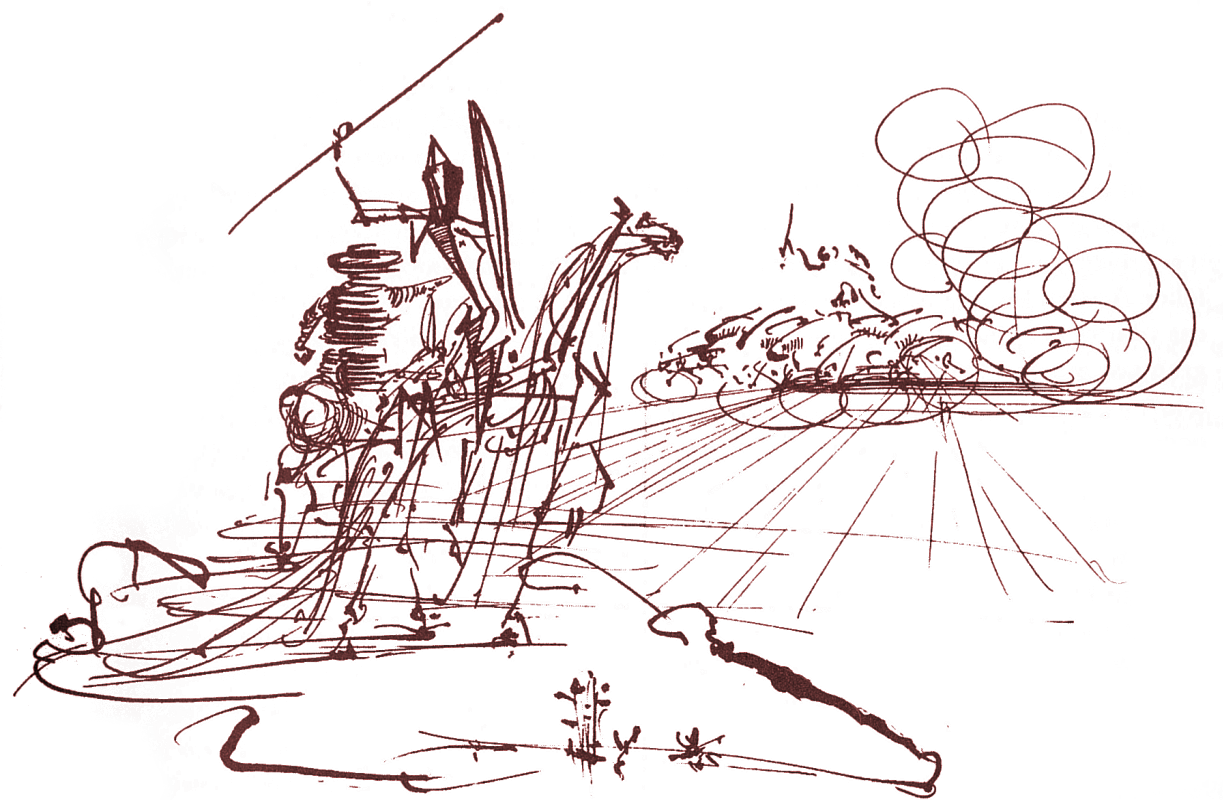

Yukio Mishima’s work has the delicacy and grace of a Japanese garden. In his book The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea, he sketches the story of a hero who falls in love and is pulled to shore. The story is seen through the eyes of young Noboru who discovers a peephole into his widowed mother’s bedroom, and, in the name of objectivity, observes her night-time exploits with her sailor lover.

This is not a sappy love story, nor is it a sex story. While erotic at times, it is handled tastefully (like sipping, not gulping, a frostie), and does not indulge itself in overly-erotic description, though it artfully evokes the proper emotions.

The plot grows organic, though beautifully tended, from weather and garden imageries that set the mood of the characters and the tone of the scene.

Overall, the book is marked by symmetry and grace, with the timeless sort of love story that would make a good Disney movie if it were subjected to animation.

As in a “classic” love story, the male/female roles are stereotyped, the woman being the owner of a clothing store that caters to a wealthy clientele and the keeper of a home (woman as domestic, comfort-seeking materialist). While the man is a sailor who is enamored of the freedom of the seas (man as eternal, roaming bachelor).

It is essentially the story of a hero through the eyes of a boy and illustrates the adage, “If we touch our idols the gilt rubs off on our hands.”

Mishima is the author of many beautiful books. In fact, he had just finished a four-book series on the day of his death. He committed ritual seppuku, a traditional form of Japanese warrior-suicide in which a warrior dies by cuts open his own stomach. Mishima had just delivered a nationalistic address to the elite army that formerly served the emperor, encouraging them to take up arms and serve the emperor in rebellion against the modern government. He was unable to rouse the pro-imperial ardor that he had hoped for, and, in despair, chose death.

The series is regarded as his last will and testament to the world. It is the story of a soul that desperately seeks to escape the cycle of death and rebirth. The first book is called Spring Snow; a tale of a narcissistic, wealthy young boy who falls in love.

It would be a mistake to regard Mishima as sentimental. The Japanese aesthetic admires the beauty of the rose but has a high regard for the steel of the sword. Mishima’s work particularly exemplifies this dual nature.

His psychological portraits are complete, but darkly beautiful and fraught with self-love. Mishima’s primary theme is that of the Zen quest to kill the ego. His philosophical roots go deep without intruding on the balance of the plot.