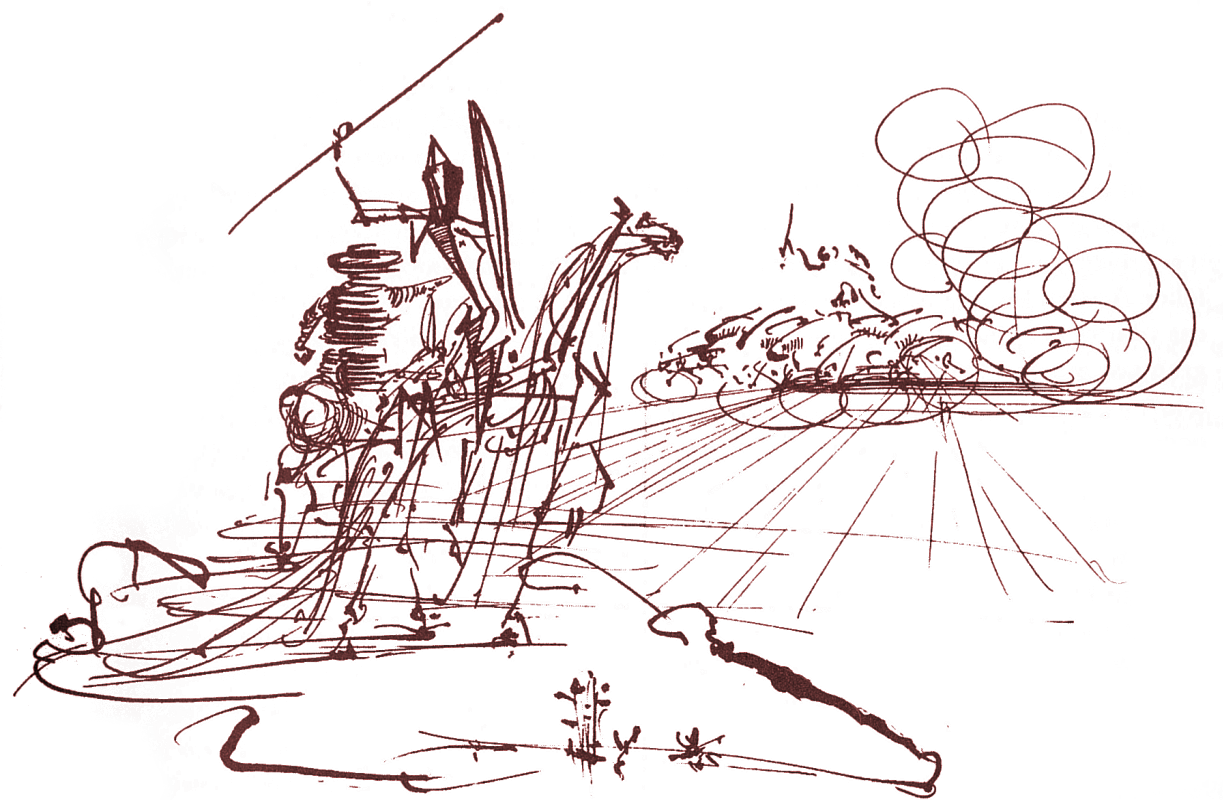

They look like big, good, strong hands, don't they. I always thought that's what they were. Ahh, my little friends, the little man with his racing snail. The nighthawk. Even the stupid bat. I couldn't hold on to them. the Nothing pulled them right out of my hands. I failed.

-Rock-biter, in The Neverending Story

In the movie "The Neverending Story," there's an alternate reality called Fantasia made up of all the hopes and dreams of humankind. But gradually people have stopped believing, hoping, dreaming, and wishing. And so a mysterious someone seized the opportunity and unleashed a dark void that gradually devours all the beautiful creations. The Nothing. The creatures of Fantasia are powerless to stop it. Why was the Nothing unleashed?

I write in response to “Idolatry of God” by Peter Rollins. Much of what Rollins writes is beautiful, and is designed to break evangelicals free from their slavery to propositional belief rather than lived faith. Rollins’ thought emerges from his own experience of radical conversion, and a later experience of God as idolatrous. Now he finds God in the midst of life. This answers some of the questions that arose from the dialogue between Micah Bales, Peter Rollins, and others (Storify). This is my second post in response to this dialog, my first can be found here.

Rollins’ personal experience of God is very valuable, and I think he’s doing some very important work in bringing attention to what we’ve made taboo in our triumphalist Christianity. In my experience, God teaches us to be faithful in our flesh through absence.

I have chosen this dialogue because few Christian thinkers are engaging seriously in poststructuralist thought. I am, as it were, a post-poststructuralist, having studied the logicians and a few of the postmodernists in college and converting to Christianity both through and out of my experience of meaninglessness in academia, in pursuit of social justice, while serving a six-month prison term for social justice. My central problem with Rollins’ work is that he’s not serious enough about the problem of evil, the power of idolatrous capitalism in our world. His system is not robust enough to resist the totalizing power of capitalism’s monetary system because it is squeamish in regards to the experience of God as well as the vision of a new society.

‘Nuff said. Here’s Rollins’ central thesis, as best I can present it in one quote,

"In addition to expressing a form of life that can break us free from the desire to find wholeness and satisfaction, the other freedom that the Crucifixion testifies to is liberation from that second, but deeply intertwined, oppressive system: Unbelief. We have already explored how Unbelief is formed and the way that so much of the church supports it by offering us yet another grand narrative that tells us why we are here, where we are going, and what we ought to be doing. However, what we find in the event that gave birth to Christianity is something far more powerful than one more master mythology designed to cover over our unknowing and anxiety. For here [in the crucifixion] we do not find yet another system of meaning to place alongside all the others but a type of splinter that disturbs all meaning systems and calls them into question. [emphasis mine]"

This continual revolution in belief is what Rollins calls pyrotheology. The problem is: if pyrotheology can be taken at its word, then it, too, must be splintered and burnt.

If pyrotheology has no objections to being burnt, then we can move on to new ideas. But if it does object, then pyrotheology is a grand narrative about how we ought to orient ourselves towards the world and other worldviews, as ones who splinter meaning continually. In this way, pyrotheology is yet another grand narrative, another meaning, another conversion. But as Wittgenstein puts it, "A doubt which doubts all things would not be a doubt." That is to say, after burning all things, we are left to evaluate the ashes, with the same anxieties.

So let us evaluate pyrotheology on its merits: as a thing, rather than as a nothing, as a theology, rather than a pyrotheology.

Deconstructionism is like the Gmork, the wolf servant of the Nothing's master who lives within Fantasia. If you set the Gmork loose in your Fantasia (your symbolic world of hopes and dreams: your personal theology) it paves the way for the Nothing to devour your world. But the Nothing is a fiction. There is no Nothing, only another Something. There is no unbelief, only belief. No meaninglessness, only meanings. No godlessness, only gods. The Nothing simply serves as a transition from one world of belief to the next. And in the darkness, many of us do not encounter God. Sometimes, in the darkness, we experience apathy and accept a drab, meaningless world.

The Totalizing Power of Capitalism and the State

As he relates experiences of Soviet totalitarianism, Milan Kundera, in the novel "The Joke," tells of a fundamentalist communist who believes absolutely in the Party and betrays her admirer. On the other hand, Czeslaw Milosz, in "The Captive Mind" writes of those intellectuals in Stalin-controlled Poland who collaborate with communism because they experience doubt, apathy, or cynicism: a failure of hope. Either unbelief, or certainty and hope in the wrong thing, can be made to serve the false idol of the communist state. I believe that instead we must strive, humbly, seeking after the Holy Spirit, towards good beliefs, hopes, and dreams, towards meaning.

We who live in the United States exist within a form of totalizing control different from communism. Gradually, our world of hopes and dreams has been transformed into a gasoline engine that pulls our global economic system. In the first world, we dream in advertisements, and we awaken to work, more work, that we use to realize our dreams of owning things, more things. For those that do not participate... the United States has the highest documented incarceration rate in the world. Capitalism is the owner of the Nothing that destroys and rebuilds our hopes and dreams in its own image.

Meanwhile, in the developing world, billions are expiring, treated as cogs in machines, fired when their factory or agricultural employers have used up their bodies, and the earth groans, boiling under an overheating atmosphere.

Money is the totalizing “Fantasia” of capitalism and serves to justify the inequalities in the world. How deeply this cuts. I think we often don’t even see how powerful our monetary system is:

"...today we produce our own talismans, our own systems of magic symbology, and indeed affect physical reality through them. A few numbers change here and there, and thousands of workers erect a skyscraper. Some other numbers change, and a venerable business shuts its doors. The foreign debt of a Third World country, again mere numbers in a computer, consigns its people to endless enslavement producing commodity goods that are shipped abroad. College students, ridden with anxiety, deny their dreams and hurry into the workforce to pay off their student loans, their very will subject to a piece of paper with magical symbols (“Account Statement”) sent to them once every moon, like some magical chit in a voodoo cult. These slips of paper that we call money, these electronic blips, bear a potent magic indeed!"

Charles Esenstien, Sacred Economics

This is what true idolatry is: a life lived enthralled by a system that chokes the world and itself. Beside this, the idolatry of our incomplete pictures of God pales. Make no mistake, we live in an Empire, and we must resist, or we will be swallowed by the Nothing and converted to capitalism. Our call is to build an alternate spirituality and culture that can undo the colonizing work of Empire within us. In order to do this, we must build a robust alternate system of meaning and belief, the vision of a better world that we hope and strive towards, a Fantasia. Because we know that there can be no better world without a meaningful vision for a new reality.

"What has been is what will be,

and what has been done is what will be done;

there is nothing new under the sun."

Ecclesiastes 1:9, NRSV

The apostle Paul speaks about the partial nature of our Fantasias on this side of death:

"For we know only in part, and we prophesy only in part; but when the complete comes, the partial will come to an end. When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child; when I became an adult, I put an end to childish ways. For now we see as [through a glass, dimly], but then we will see face to face." NRSV with a revision

Paul’s Dim Glass is a Fantasia

Even though Paul likely got himself killed because of his actions and beliefs, he comments on the incompleteness of his understandings and theologies. Why? The partial nature of our representation of God is trivially true because, like our understandings of objective reality itself, our understandings of God come to us through our senses which are symbolic representations of secondary phenomenon. Our retina absorbs light reflected off of objects. We do not encounter reality directly. We live in a Fantasia from which we cannot escape.

Cognitive scientist Allison Gopnik describe how children build logically consistent worlds gradually through experimentation. Children’s worlds seem fantastic to us: Fantasias. But our worlds, when experienced more objectively, are also Fantasias. We are separated from the reality of objective existence and God. All we have are pseudo-logical fantasy worlds constructed from sensory data. Fantasia in the The Neverending Story, however, functions in a more specific way, as a world of dreams and hopes that resists the pull of an alternate system of meaning: the drabness of everyday life. I use Fantasia as a realist, not a romantic, to point to both the absurdity and necessity of our visions of reality and theology. Our Fantasias create our material communities as we give them power.

Material Community Towards Building Fantasia

Because our visions, meanings, and theologies are incomplete, Paul beseeches us to love one another. But directly afterwards, we must express this love communally as the Acts church did, by cultivating material practices rooted in just living that separates us from a culture that will ultimately render this planet uninhabitable. This frees us from the "endless pursuit of satisfaction" (as Rollins puts it) that is ultimately bankrupting our our bodies, our ecosystems, and our planet.

To do this we must build another community that incorporates all parts of the person, our loves, our beliefs, our bodies in liturgy, our money in shared economies, our food in common meals, and our lives in community. Theology and belief are tools, and God knows that we will need all of our tools if we are to resist the Nothing. This alternative community is what we call the church.

The Church as a Demarcated Space for Healing from Trauma

Our church has failed us here in the first world. It has not been what I suggest it must be. The church has collaborated with injustice as frequently as it has worked for the abolition of slavery.

But what is attractive to me about the church's tribal model of membership is that we can create mission and purpose within a demarcated communal space, setting up culture that can resist colonization by capitalism.

I'm not sure how Rollins would feel about my hard-edged space. He says, "For Paul it is this very loss of identity that identifies us with Christ. As we experience the loss of the operative power of our identity, we thus touch upon that experience of utter loss expressed in the Crucifixion of Christ." Rollins enjoins us to engage in continual dialog with the other by placing "...ourselves beneath them in the sense of allowing their views to challenge and unsettle our own."

I believe, like Rollins, we must crucify our identities in the world to become a part of the church-tribe. But there is a danger in presuming that we don't have beliefs, or that we've truly broken from the oppressive orders of the world. Anti-oppression culture calls this color-blindness. Rollins may not advocate for class and color blindness, but identity blindness is the charism of our culture, which, I believe, swallows us unless we specifically guard against it. Identity politics is a response to this swallowing of identity in the marketplace.

When we believe that we believe nothing, or when we believe we have no personal or communal identity, our identities and and beliefs become submerged, pushed into the realm of the taboo, unable to be openly addressed. In this space, after the burning of all identities, we're left to sort through our identities. And we find that we're actually who we were in the totalizing system of money: slave and free, man and woman, Jew and Greek. Because we live in a culture of inequality, we have to create systems that consciously undo inequality.

Instead of continually welcoming others to unsettle our community, I suggest that we ground our space in the welcoming of oppressed others. The space we create, our community, must be an intentionally safe space for those who have experienced the traumas of our world, the violences of our economic and military systems. We cannot continually unsettle this ground.

This is because any space that seeks to welcome the traumatized must create a structure that can resist the predator. We may welcome the predator in the spirit of radical hospitality, but within boundaries. In the fullness of time, the lion will lay down with the lamb. But if we create a space that questions the framework of love and respect itself, the lion will eat the lamb, and all of our spaces will be dens for lions. If we do not create a safe space for women, queer folks, and those oppressed because of race or minority status, by specifically addressing and “vomiting out” beliefs that are re-traumatizing, like racism or sexism, we will gradually become like the culture of Empire that surrounds us. Some worldviews cannot be allowed to unsettle us, or we cannot create a space that is rooted in love and mutual respect. The Gospel is clear that we are not all striving towards God. Some have given up hope, and, if they choose not to walk the path, they must exist outside the church or they will re-traumatize those that are walking the path.

The problem for me, and likely Rollins, is that the American Church has actually encoded as doctrine sexism, racism, or oppression towards queer folks. I suggest that we exorcise this demonic spirit of oppression rather than our certainties about God.

Nonviolent Resistance to Empire

When we create a safe space, we can cultivate love in community. Out of this positive experience of community, we will be called by our God to confront the powers and principalities of this world in love and truth-firmness as capitalism gradually devours itself. This is experienced as a fire in the bones.

I constantly interrogate my own beliefs. But I have not experienced continual self-interrogation as the spiritual substrate for Ghandi's satyagraha (truth-firmness). Rather, my doubts are purged away in action. Nonviolence is firm in its existential posture towards evil.

I have never wanted to be consumed by the fire in order to end injustice, to have my bones crushed and mutilated, or be burned as a candle, because of my self-interrogating doubt. Martyrs like Jesus Christ need a grand narrative, just as Victor Frankl did, as dimly seen as it might be. In these times, our crucifixion will be material, not psychological.

Think about Martin Luther King's words, "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice." This was what gives us the courage to throw ourselves into the gears, a grand narrative of justice, a vision of a better world. “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing," Arundhati Roy.

Martyrs, prophets, and activists, because of their position so radically outside the culture, rely upon God for their inner light and inspiration, as they gain the courage to confront the death-system.

The “Nothing” is Well-Loved

In the Neverending Story, Atreyu asks the Gmork why his master unleashed the Nothing on Fantasia, and the Gmork tells him, “People who have no hopes are easy to control.”

The easiest and most popular response to belief in our postmodern culture is deconstruction. With the deconstruction of meaning, we are free to participate wholly in the capitalist economy, the submerged meaning system of our culture. The most difficult thing is to build something beautiful: an alternate system of meaning. And for that, we need God.

I believe that God who is love gives us our hopes and our meanings. God is a being outside of ourselves who woos us to Godself. But God cannot be contained, and God will not necessarily satisfy us or give us internal peace. God may not even be continually present in our lives. Rather, God calls us to a life of service or even to death on a cross.

And this is the crucifixion, the crucifixion of meaning outside of God and love for neighbor.

Amen.

The threads that began this dialogue can be found on this Storify. Thanks also to Suzannah Paul over at The Smitten Word for bringing identity issues to the fore in her post, "tragically hip: privilege & the emerging church.".